Continuing on the loop optimizations covered in my last post here. Let’s look at one of the key loop optimization in detail today. Loop unroll as the name suggests tries to take the key aspect of a loop out of the loop i.e. looping xD. It achieves so by copying the instructions inside the loop and reducing the number of loop iterations or completely getting rid of them as we will see now. I’ll try to build up from basic examples to how it is implemented in the LLVM compiler.

Loop unroll

At a high level we are trying to achieve something like this:

{

for(int i = 1; i < 5; i++)

dst[i] = dst[i-1] + src[i];

}

After fully unrolling the above loop

{

int i = 1;

dst[i] = dst[i-1] + src[i];

dst[i+1] = dst[i] + src[i+1];

dst[i+2] = dst[i+1] + src[i+2];

dst[i+3] = dst[i+2] + src[i+3];

dst[i+4] = dst[i+3] + src[i+4];

}

Let’s talk about the actual benefits it provides.

- Less Branching: : The most obvious one is it reduces branches (we don’t have to go from the end of the loop to the beginning after each iteration). Branching is one of the most expensive operations for a processor. Other than modifying the program counter it also messes up instruction caching.

- Increased parallelization: Most modern processors have some form of instruction parallelization available. Vector instructions, SIMD, etc. The gist of it is a single instruction is performing the same operation on multiple data points provided that the instructions are independent of each other. (Notice that this is not the case in our example above).

- Dependent optimizations: Most of the code optimizations will be better off if we can eliminate the loop and end up doing optimizations on linear code. Moreover even when we can’t fully unroll the loop, unrolling some iterations can help us get rid of complex code inside the loop (we’ll explore this further in Loop peeling and runtime unrolling).

There are certainly cases when unrolling does more harm than good.

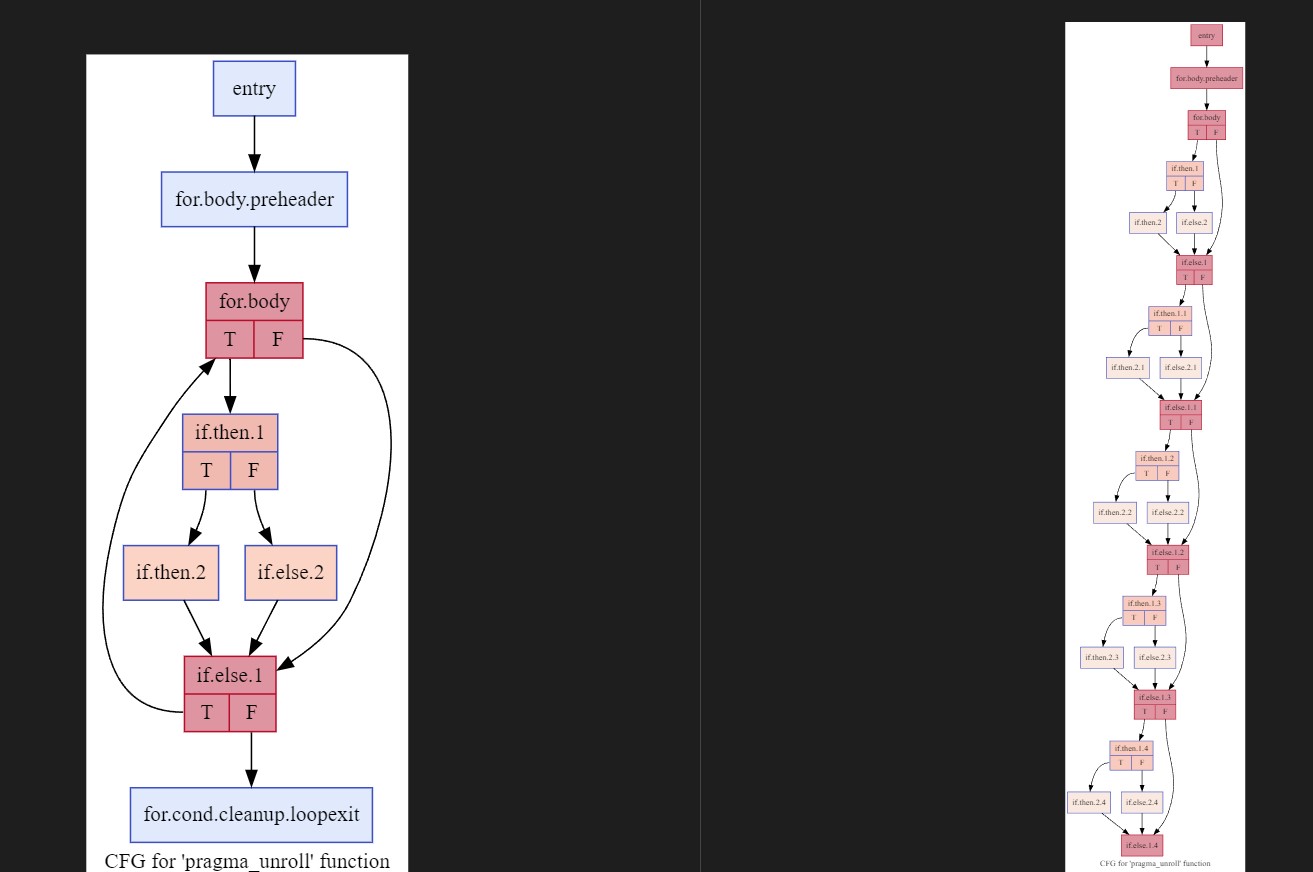

Complicates CFG: When the loop structure inside is complex (contains branches) unrolling it will end up creating even more repetitive branches. Observe what happens to control flow graph when the IR here is unrolled (I have kept the code blocks empty for simplified view).

Increased Register pressure: Less registers, more demand -> more register pressure. If there are memory instructions(loads/stores) inside the loop copying them while unrolling will end up eating up all our registers. Look at this example. Notice how the load/stores exploded. Normally llvm won’t do this aggressive unrolling (we’ll explore this further in computing unroll count section) I tried to artificially induce it here to demonstrate the problem.

There are more disadvantages, I will cover a few more when we look at the compiler heuristics for unrolling and the cases when the compiler decides not to unroll.

Types of Unrolling that LLVM performs

1) Loop Peeling

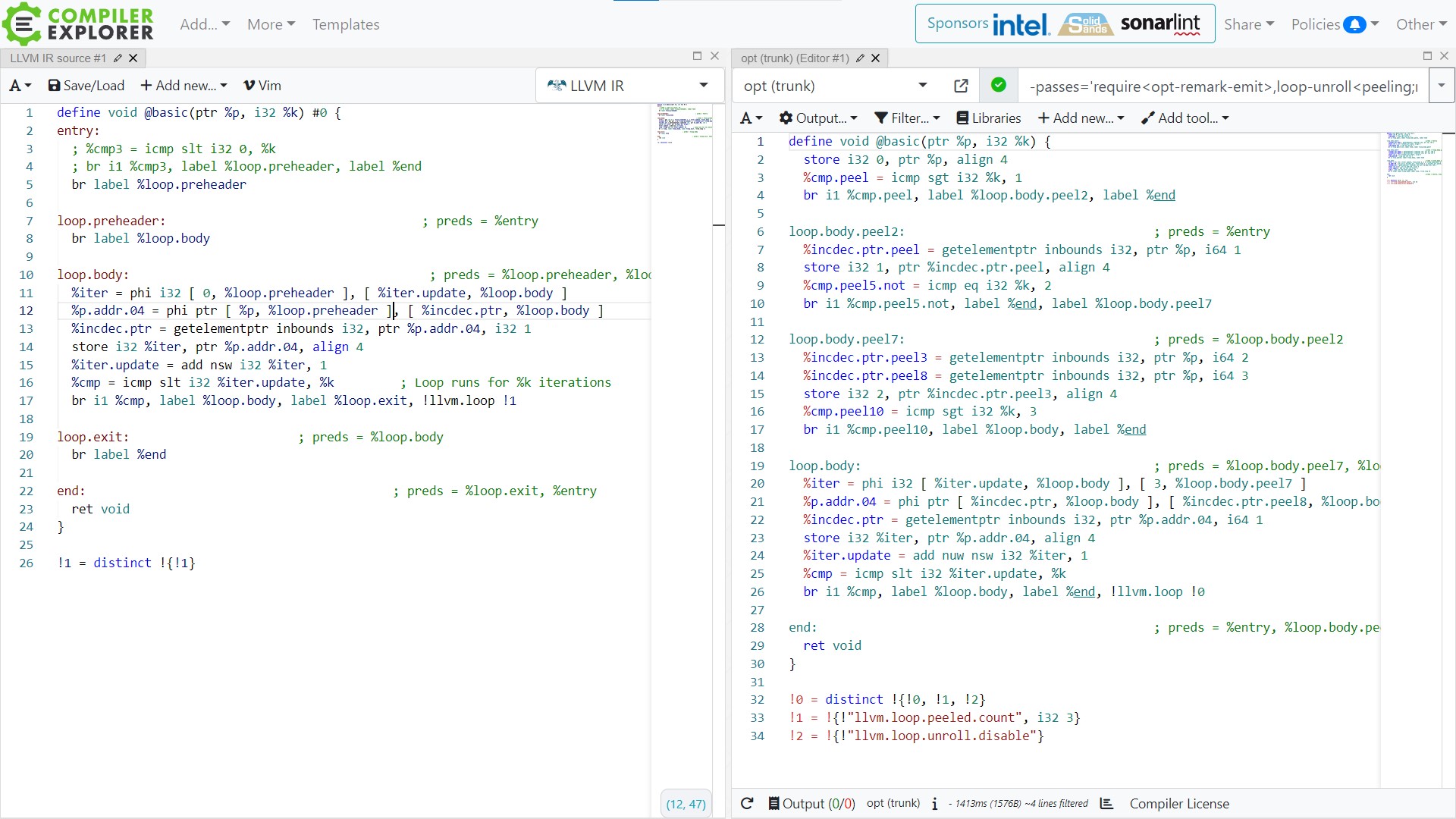

Loop peeling works on the idea that the trip count of a loop is unknown and can’t be statically computed during compile time. We can still move the first few iterations out of the loop and execute them sequentially enabling them for straight-line code optimizations. In the example below first 2 iterations of the loop are moved out(notice the first line in “loop.body” basic block, it starts from the 0th iteration before and the 3rd after). For now, ignore the compiler options used to trigger this behavior.

- Loop peeling is not a separate pass in LLVM it is tightly coupled with LoopUnrollPass and is called from there before it attempts unrolling.

- It does not peel out the iterations as a straight line code rather each iteration is peeled out separately as a sequence of basic blocks. You can observe this in the example above by removing the ‘simplifycfg’ flag from the compile command.

- Peeling is turned on by default by LLVM however you can switch it off using ’-unroll-allow-peeling=false’ option.

- LLVM does not try to perform peeling and unrolling together, if a loop is peeled it is marked not to be checked for unrolling further.

- The logic for peeling resides in llvm::peelLoop function.

1.1 Calculating the peel iterations

How does the llvm compiler calculate the iterations to peel? In the order checked by LLVM:

- The loop should be peelable, checked in llvm::canPeel(). If that returns false no attempt at peeling is done.

- If the user provides a peel count like in our example above, then that will be used for peel iterations.

- Skip peeling if disabled explicitly by the user (-unroll-allow-peeling=false).

- Skip if even one peel iteration can’t be performed.

- Eliminate phi nodes: Calculate minimum peel iterations required to make all phis invariant. Making loop variables invariant is one major reason we try peeling in the first place (explained in section 1.2).

- Eliminate if conditions: Calculate the min peel count required to eliminate ’ if conditions’ in the loop body (explained in section 1.3).

- Also make sure the peel count computed in steps 6, and 7 is not greater than MaxPeelCount(if provided by the user explicitly via a CLI option or a pragma).

1.2 Making phi nodes invariant via peeling

Invariant here means independent of loop iterations, e.g., If a variable value inside a loop does not depend on the iteration number it is said to be loop invariant and vice versa. The same goes for phi nodes, and when a phi node becomes invariant it can be eliminated.

Let’s look at an example directly taken from LoopPeel.cpp

void g(int);

void binary() {

int x = 0;

int y = 0;

int a = 0;

for(int i = 0; i <100000; ++i) {

g(x);

x = y;

g(a);

y = a + 1;

a = 5;

}

}

In it’s current form the LLVM-IR for the for loop above looks somewhat like this with 4 phi nodes.

%i = phi i32 [ 0, %entry ], [ %inc, %if.end ]

%a = phi i32 [ 0, %entry ], [ 5, %if.end ]

%y = phi i32 [ 0, %entry ], [ %add, %if.end ]

%x = phi i32 [ 0, %entry ], [ %y, %if.end ]

...

tail call void @_Z1gi(i32 signext %x)

tail call void @_Z1gi(i32 signext %a)

%add = add nuw nsw i32 %a, 1

%inc = add nuw nsw i32 %i, 1

%exitcond = icmp eq i32 %inc, 100000

br i1 %exitcond, label %for.cond.cleanup, label %for.body

Peeling this loop by 3 will make x, y and a known!! Lets see how:

void g(int);

void binary() {

int x = 0;

int y = 0;

int a = 0;

// 1st iteration

g(x); g(0)

x = y; x = 0

g(a); g(0)

y = a + 1; y = 0 + 1

a = 5; a = 5

// 2nd iteration

g(x); g(0)

x = y; x = 1

g(a); g(5)

y = a + 1; y = 5 + 1

a = 5; a = 5

// 3rd iteration

g(x); g(1)

x = y; x = 6

g(a); g(5)

y = a + 1; y = 5 + 1

a = 5; a = 5

// 4th iteration

g(x); g(6)

x = y; x = 6

g(a); g(5)

y = a + 1; y = 5 + 1

a = 5; a = 5

// 5th iteration

g(x); g(6)

x = y; x = 6

g(a); g(5)

y = a + 1; y = 5 + 1

a = 5; a = 5

for(int i = 5; i <100000; ++i) {

g(x);

x = y;

g(a);

y = a + 1;

a = 5;

}

}

The arguments for the calls to g will become known after 3 iterations of the loop, because the phi nodes values become known after 3 iterations of the loop (i.e., they are known on the 4th iteration, so peel 3 iterations).

The first iteration has g(0), g(0); the second has g(0), g(5); the third has g(1), g(5) and the fourth (and all subsequent) have g(6), g(5). Now consider the phi nodes:

- %a is a phi with constants so it is determined after iteration 1.

- %y is a phi based on a constant and %a so it is determined on the iteration after %a is determined, so iteration 2.

- %x is a phi based on a constant and %y so it is determined on the iteration after %y, so iteration 3.

- %i is based on itself (and is an induction variable) so it is never determined.

This means that peeling off 3 iterations will result in being able to remove the phi nodes for %a, %y, and %x. The arguments for the corresponding calls to g are determined and the code for computing x, y, and a can be removed.

As expected 3 iterations of the loop with calls to {g(0), g(0)}, {g(0), g(1)}, {g(1), g(5)}

are peeled out. Loop now starts from the 4th iteration with 3 phi nodes eliminated and calls to

{g(6), g(5)} in each remaining iteration.

As expected 3 iterations of the loop with calls to {g(0), g(0)}, {g(0), g(1)}, {g(1), g(5)}

are peeled out. Loop now starts from the 4th iteration with 3 phi nodes eliminated and calls to

{g(6), g(5)} in each remaining iteration.

1.3 Eliminating if conditions inside loops via peeling

Consider below simple example

for (i = 0; i < n; i++)

if (i < 2)

A

else

B, C

}

Obviously peeling the loop by 2 will help us get rid of this ‘conditional if’ in every iteration.

A1

A2

for (i = 2; i < n; i++)

B, C

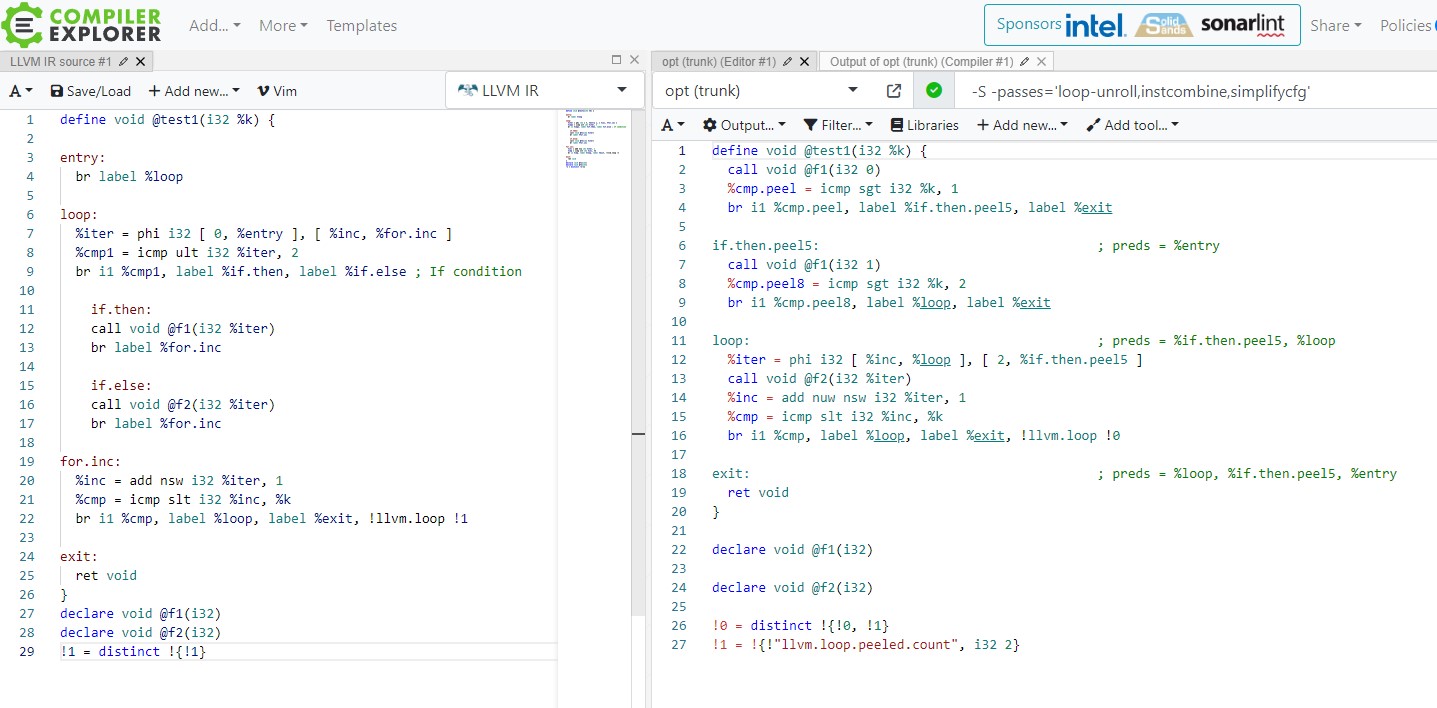

Complete example

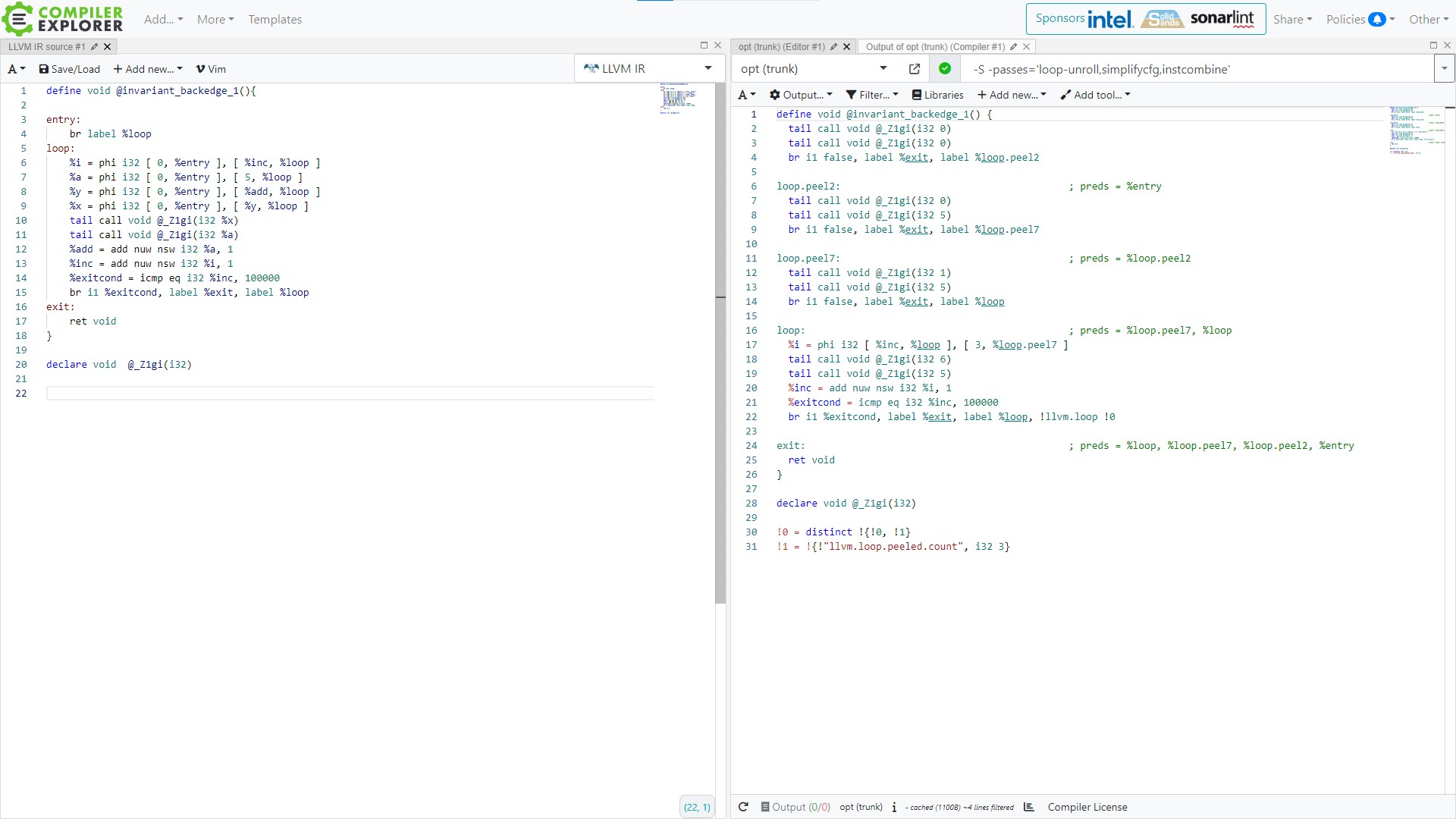

As expected 2 iterations are peeled out to eliminate the ‘if’ condition inside the loop. Notice

how the loop now starts on 3rd iteration and called to f1(0) and f1(1) are moved out of the loop.

As expected 2 iterations are peeled out to eliminate the ‘if’ condition inside the loop. Notice

how the loop now starts on 3rd iteration and called to f1(0) and f1(1) are moved out of the loop.

2) Full Unroll

LLVM has 2 registered unrolling passes LoopUnrollPass and LoopFullUnrollPass. Both these passes rely on same unrolling mechanism and use the same interface defined in LLVM::tryUnrollLoop() function. Only differentiating factors are the function parameters passed to them.

- FullUnrollPass will only attempt to fully unroll the loop i.e get rid of the loop entirely and bail out if that’s not possible.

- LoopUnrollPass will try both, full unroll, failing to do so, try runtime/partial unroll. (For now, consider partial unroll similar to peeling when some iterations are moved out and loop size is decreased).

- Full unroll pass can be run before inlining and LoopUnrollPass is run only after inlining(though it can also perform full unroll as we’ll see).

We can’t afford to partially unroll the loop before inlining as the loop count variable might become a compile time constant after inlining. Consider below example

void f(int n){

for(int i = 0; i < n; ++i)

A;

}

void main(){

f(3);

}

If the unroller tries to unroll the loop in f() it won’t be able to deduct the loop count which is a function parameter hence can’t fully unroll it, however, if we are to force it to perform unrolling it will end up partially unrolling it. Which will disable the loop for further unrolling, and we will miss out on this easy optimization. Instead, LoopFullUnrollPass will bail out and LoopUnrollPass will take care of it after inlining.

void main(){

for(int i = 0; i < 3; ++i)

A;

}

// To,

void main(){

A1;

A2;

A3;

}

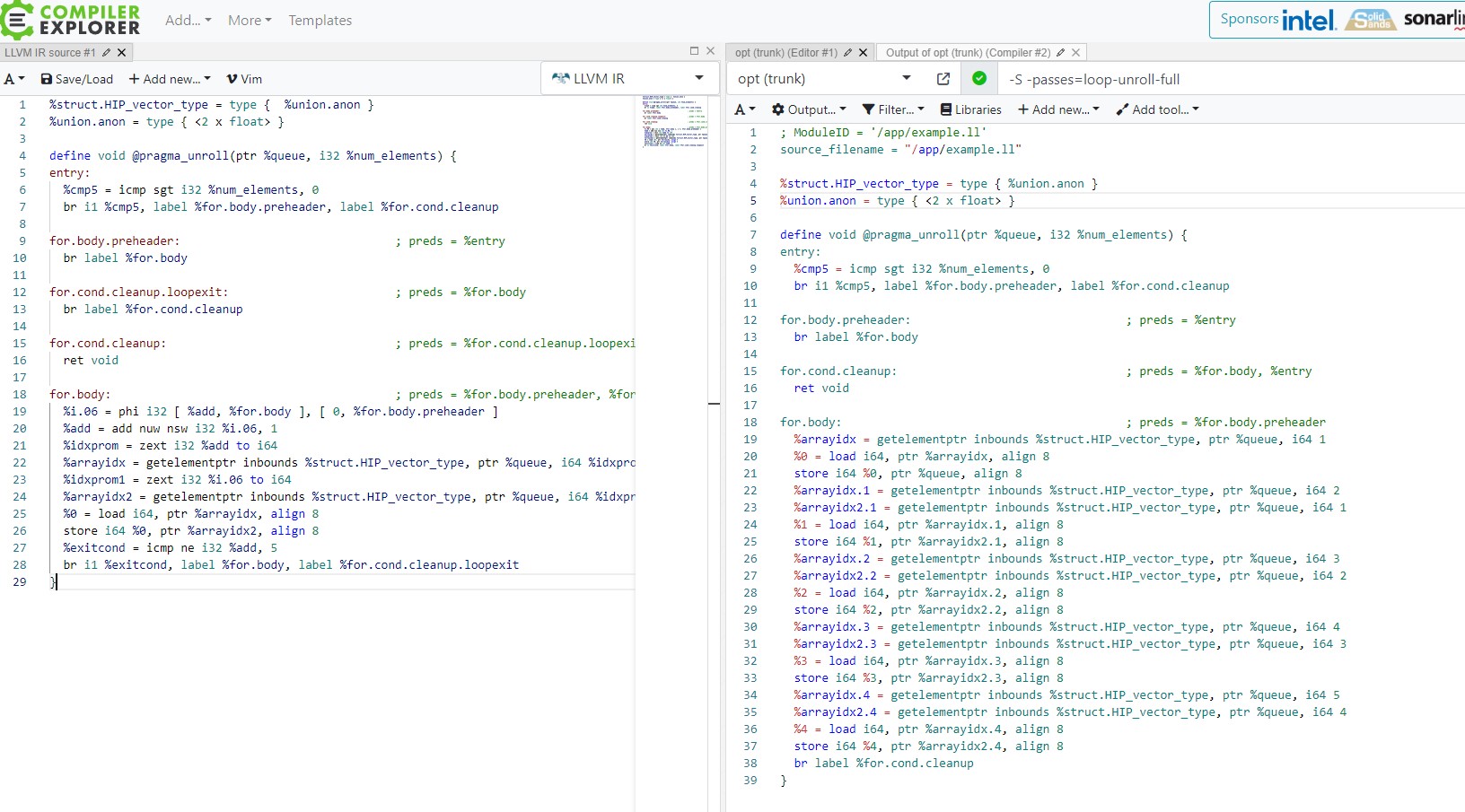

As you can see a simple for loop in ‘for.body’ running for 5 iterations is completely transformed into sequential code.

Have a look what happens when a nested loop is fully unrolled. In this example you can see the inner loop is flattened by 3 and this flattened code is further repeated 5 times (outer loop iteration count).

3) Runtime Unroll

Runtime unrolling or partial unrolling comes into the picture when we cannot determine the exact trip count of a loop. Working:

- Decide on an unroll-count factor, default is 8 but can also be explicitly passed by the user, as well as can be calculated to a more optimal value by the compiler.

- Flatten the loop by unroll-count (by copying the instructions inside as many times).

- The total iteration count will now become (original-count / unroll-count).

- Add an additional loop (called remainder loop) running for (original-count % unroll-count) iterations.

Let’s try to look at it via a high level example

void fun(int n, int arr[]){

for(int i = 0; i < n; ++i)

arr[i] = i + arr[i];

}

// For this example with unroll-count 3 this loop transforms into

void fun(int n, int arr[]){

// partially unrolled loop

for(int i = 0; i < n; i+=3){

arr[i] = i + arr[i];

arr[i+1] = i+1 + arr[i+1];

arr[i+2] = i+2 + arr[i+2];

}

// remainder loop

int rem = n % 3;

for(int i = 0; i < rem; ++i){

int ind = n - rem + i;

arr[ind] = ind + arr[ind];

}

}

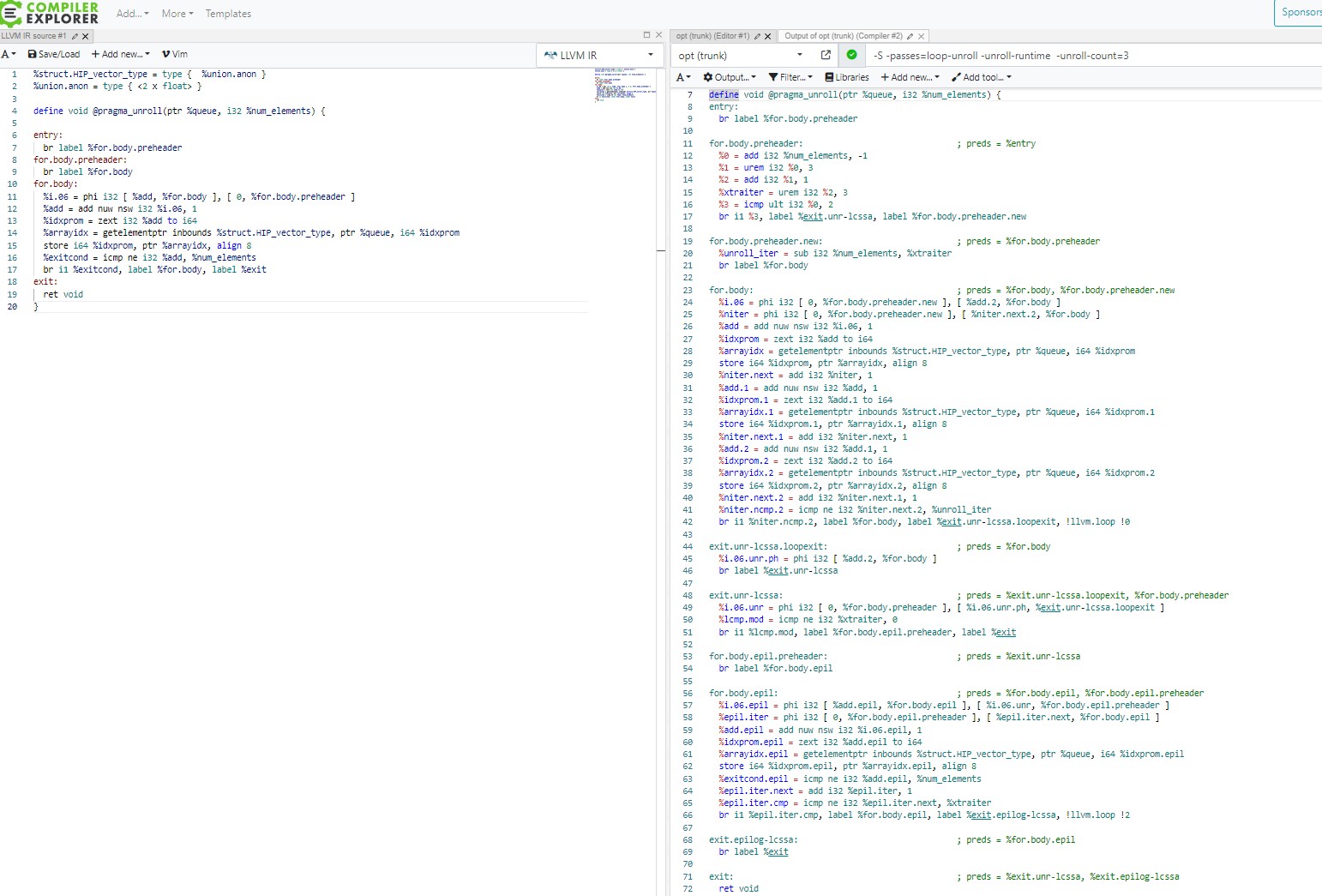

Have a look at this LLVM example for partial unrolling.

- The runtime unroll-count is explicitly set to 3.

- The loop inside for.body is now 3 times the size and the iteration variable increases by 3 every iteration(see %add in lines 26, 31, 36).

- You can notice that the trip count of this loop is decreased by the remainder amount (lines 15,20).

- Block ‘for.body.epil’ represents the remainder loop. It starts from where the previous loop ends to the original trip count.

3.1 How unrolling count is computed by the compiler

In the order treated by LLVM

- If -unroll-count is specified that will be used. See.

- If pragma unrolls are specified than those are used. (There are a whole lot of loop unroll related pragmas, mentioned some in later section). eg

#pragma unroll 4

for(int i = 0; i < 50; i++)

A, B;

// This unroll information will be embedded inside the IR as loop metadata and will

// look sth like this "!0 = !{!"llvm.loop.unroll.count", i32 4}".

// Similarly #pragma unroll disable, translates to "llvm.loop.unroll.disable" metadata.

- If it’s possible to do full unrolling do that.

- Try peeling.

- Try partial unroll.

4) LoopUnrollAndJam and LoopFlatten

There are 2 more loop unrolling optimizations passes available in LLVM, these are disabled by default and have to explicitly turned on via ’enable-unroll-and-jam’ and ’enable-loop-flatten’ options respectively.

I’m not gonna discuss these passes here, you can read about them on the pull requests that introduced them.

Loop unroll heuristics

Compiler options exposed to end user

LLVM has a plethora of compiler option which allow you to have a very tight control over peeling and unrolling. Options defined in LoopUnrollPass.cpp and LoopPeel.cpp. You can explore them yourself in the source files.

opt --help-hidden | grep "peel\|unroll"

--allow-unroll-and-jam - Allows loops to be unroll-and-jammed.

--amdgpu-unroll-max-block-to-analyze=<uint> - Inner loop block size threshold to analyze in unroll for AMDGPU

--amdgpu-unroll-runtime-local - Allow runtime unroll for AMDGPU if local memory used in a loop

--amdgpu-unroll-threshold-if=<uint> - Unroll threshold increment for AMDGPU for each if statement inside loop

--amdgpu-unroll-threshold-local=<uint> - Unroll threshold for AMDGPU if local memory used in a loop

--amdgpu-unroll-threshold-private=<uint> - Unroll threshold for AMDGPU if private memory used in a loop

--disable-advanced-peeling - Disable advance peeling. Issues for convergent targets (D134803).

--disable-loop-unrolling - Disable loop unrolling in all relevant passes

--enable-unroll-and-jam - Enable Unroll And Jam Pass

--flat-loop-tripcount-threshold=<uint> - If the runtime tripcount for the loop is lower than the threshold, the loop is considered as flat and will be less aggressively unrolled.

--forget-scev-loop-unroll - Forget everything in SCEV when doing LoopUnroll, instead of just the current top-most loop. This is sometimes preferred to reduce compile time.

--loop-unroll - Unroll loops

--loop-fusion-peel-max-count=<uint> - Max number of iterations to be peeled from a loop, such that fusion can take place

--openmp-ir-builder-unroll-threshold-factor=<number> - Factor for the unroll threshold to account for code simplifications still taking place

--partial-unrolling-threshold=<uint> - Threshold for partial unrolling

--pipeliner-experimental-cg - Use the experimental peeling code generator for software pipelining

--pragma-unroll-and-jam-threshold=<uint> - Unrolled size limit for loops with an unroll_and_jam(full) or unroll_count pragma.

--pragma-unroll-threshold=<uint> - Unrolled size limit for loops with an unroll(full) or unroll_count pragma.

--switch-peel-threshold=<uint> - Set the case probability threshold for peeling the case from a switch statement. A value greater than 100 will void this optimization

--unroll-allow-loop-nests-peeling - Allows loop nests to be peeled.

--unroll-allow-partial - Allows loops to be partially unrolled until -unroll-threshold loop size is reached.

--unroll-allow-peeling - Allows loops to be peeled when the dynamic trip count is known to be low.

--unroll-allow-remainder - Allow generation of a loop remainder (extra iterations) when unrolling a loop.

--unroll-and-jam-count=<uint> - Use this unroll count for all loops including those with unroll_and_jam_count pragma values, for testing purposes

--unroll-and-jam-threshold=<uint> - Threshold to use for inner loop when doing unroll and jam.

--unroll-count=<uint> - Use this unroll count for all loops including those with unroll_count pragma values, for testing purposes

--unroll-force-peel-count=<uint> - Force a peel count regardless of profiling information.

--unroll-full-max-count=<uint> - Set the max unroll count for full unrolling, for testing purposes

--unroll-max-count=<uint> - Set the max unroll count for partial and runtime unrolling, fortesting purposes

--unroll-max-iteration-count-to-analyze=<uint> - Don't allow loop unrolling to simulate more than this number ofiterations when checking full unroll profitability

--unroll-max-percent-threshold-boost=<uint> - The maximum 'boost' (represented as a percentage >= 100) applied to the threshold when aggressively unrolling a loop due to the dynamic cost savings. If completely unrolling a loop will reduce the total runtime from X to Y, we boost the loop unroll threshold to DefaultThreshold*std::min(MaxPercentThresholdBoost, X/Y). This limit avoids excessive code bloat.

--unroll-max-upperbound=<uint> - The max of trip count upper bound that is considered in unrolling

--unroll-optsize-threshold=<uint> - The cost threshold for loop unrolling when optimizing for size

--unroll-partial-threshold=<uint> - The cost threshold for partial loop unrolling

--unroll-peel-count=<uint> - Set the unroll peeling count, for testing purposes

--unroll-peel-max-count=<uint> - Max average trip count which will cause loop peeling.

--unroll-remainder - Allow the loop remainder to be unrolled.

--unroll-revisit-child-loops - Enqueue and re-visit child loops in the loop PM after unrolling. This shouldn't typically be needed as child loops (or their clones) were already visited.

--unroll-runtime - Unroll loops with run-time trip counts

--unroll-runtime-epilog - Allow runtime unrolled loops to be unrolled with epilog instead of prolog.

--unroll-runtime-multi-exit - Allow runtime unrolling for loops with multiple exits, when epilog is generated

--unroll-runtime-other-exit-predictable - Assume the non latch exit block to be predictable

--unroll-threshold=<uint> - The cost threshold for loop unrolling

--unroll-threshold-aggressive=<uint> - Threshold (max size of unrolled loop) to use in aggressive (O3) optimizations

--unroll-threshold-default=<uint> - Default threshold (max size of unrolled loop), used in all but O3 optimizations

--unroll-verify-domtree - Verify domtree after unrolling

--unroll-verify-loopinfo - Verify loopinfo after unrolling

Almost all of them are meant to be used for debugging purposes.

Loop unroll pragmas

I couldn’t find a complete list of unroll pragmas supported by Clang. Mentioning some of the popular ones here, all of them are self-explanatory.

- #pragma unroll(n)

- #pragma nounroll

Clang pragmas

- #pragma clang loop unroll(enable)

- #pragma clang loop unroll(disable)

- #pragma clang loop unroll(full)

- #pragma clang loop unroll_count(4)

GCC

- #pragma GCC unroll

- #pragma GCC nounroll

- #pragma GCC unroll(UNROLLCOUNT)

OpenMP

- #pragma omp unroll

- #pragma omp unroll full

- #pragma omp unroll partial

- #pragma omp unroll partial(3)

This pragma information is encoded in LLVM IR metadata.

Loop unroll metadata

Metadata allows extra information to be attached with objects(instructions, functions, loops, etc) to be referred by the Optimizer or the CodeGenerator. For example if you define your c++ loop with "#pragma nounroll" the compiler will attach "!`llvm.loop.unroll.disable" metadata with this loop object.

Similarly ’#pragma omp unroll partial(3)’, ’#pragma clang loop unroll_count(3)’, etc will end up setting

!0 = !{!"llvm.loop.unroll.count", i32 3}

Refer https://llvm.org/docs/LangRef.html#metadata for complete list of metadatas in LLVM.

Conclusion

This is still a high level overview of unrolling, there is a lot more that can be discussed such as ‘How are these passes inserted in passBuilderPipeline?’, ‘SCEV(Scalar evolution)’, ‘Loop unrolling profitability heuristics and calculations’, ‘Target unrolling preferences’, etc. You are free to explore all this stuff. :)

Thanks for reading!!